On March 28, 2024, a powerful earthquake with a magnitude of 7.7 Mw and a depth of 10 km occurred in Myanmar (Burma). It was followed by a second earthquake of 6.7 Mw and several aftershocks (35 seismic events) with magnitudes ranging from 3.5 to 5.4 Mw, as well as additional lower-magnitude tremors in the same area [1]. The disaster resulted in more than 3,500 fatalities, thousands of injuries, and millions of people affected by the earthquake [1].

The main shock focal mechanism and finite fault solution suggest that the earthquake likely occurred along the right-lateral Sagaing Fault, which lies within the fault zone marking the plate boundary between the Indian and Sunda plates [1]. This event has been analyzed using Differential Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry (DInSAR), a key satellite technique for estimating surface deformations with centimeter to millimeter accuracy, caused by seismic crises, magma intrusion, and other geodynamic processes [2-3].

An end-to-end, fully unsupervised DInSAR processing tool capable of generating co-seismic maps has been implemented at IREA-CNR [4]. This tool operates on cloud computing platforms and leverages the extensive spaceborne SAR data archive provided by the Copernicus Sentinel-1 (S1) satellite constellation, which offers SAR data under a free and open-access acquisition policy [5].

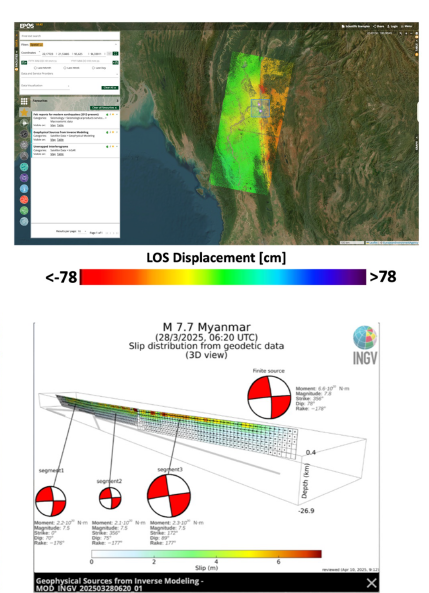

In the context of the Myanmar seismic crisis, the EPOS TCS Satellite Data services, automatically triggered by the most significant seismic events in the region, generated DInSAR products processing the SAR data collected in the area by the Copernicus Sentinel-1 constellation. As a result, multiple DInSAR products have been created for all satellite orbits (Tracks 70, 33, 106, and 143) to map the whole area interested by the seismic sequence.

The generated co-seismic DInSAR products, including deformation maps and geophysical sources from inverse modeling, have been made available in the EPOS infrastructure and are accessible through the web services of the EPOS Data Portal.

References:

USGS earthquake Catalog, available at: https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards

Massonnet, D. et al., “The displacement field of the Landers earthquake mapped by radar interferometry,” Nature, vol. 364, no. 6433, pp. 138– 142, Jul. 1993.

Burgmann, R., Rosen, P.A., Fielding, E.J., 2000. Synthetic aperture radar interferometry to measure Earth's surface topography and its deformation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 28, 169–209.

Monterroso, F., Bonano, M., De Luca, C., Lanari, R., Manunta, M., Manzo, M., Onorato, G., Zinno, I., Casu, F., 2020. A global archive of Coseismic DInSAR products obtained through unsupervised Sentinel-1 Data processing. Remote Sens. (Basel) 12 (19), 3189. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12193189.

R. Torres, P. Snoeij, D. Geudtner, D. Bibby, M. Davidson, E. Attema, P. Potin, B. Rommen, N. Floury, M. Brown, I. Traver, P. Deghaye, B. Duesmann, B. Rosich, N. Miranda, C. Bruno, M. L’Abbate, R. Croci, A. Pietropaolo, M. Huchler, and F. Rostan, 2012. GMES Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 120, pp. 9-24, 2012